I’ve been described as “resilient” more times than I can remember. I get that people mean well when they say it, especially to a Black woman, because it means we have overcome some version of a horrendous, traumatic or violent experience.

It’s important to be explicit about it because Black and brown women experiencing hardship is accepted as a normal part of life. We must expect hardship. We must expect pain. We must expect sexual violence. We must expect racial violence. We must expect professional violence. We must expect financial violence. We must expect physical and emotional abandonment. We must expect to be accused of trapping men with pregnancies.

We must expect to be blamed for rapists raping us. We must expect to have our bodies and clothing choices policed. We must expect to be ill-treated by our in-laws. We must expect to be cheated on by our partners because “that’s just how men are, baby.” We must be prepared to be cussed out and/or assaulted by men who don’t get our attention. We must expect to be undermined in the workplace. We must expect subpar treatment at hospitals that put our lives at risk.

In all of this, it is demanded that we endure. We are required to suck it up and not be problematic. We are expected to not cause a scene. We are expected to live a life that has no room, patience or empathy for our pain, our disappointment, our anger. Our rage. Because it’s our “negative emotions” that make people uncomfortable. Not the injustices we have had to live with generation after generation. Not the trauma we have fought with our lives to survive and try our best to heal from, even with the constant triggers that force us to relive that pain.

And when somebody does want to “listen” to what we have to say, we have to perform our pain. We have to be so detailed, so explicit, so graphic about our experiences because if we just say, “My experience has been ABC,” the response is often, “Oh, is that all? But you seem fine now, so we don’t need to resort to anything extreme.”

Read more | Trying to negotiate a better salary? Here’s how to know if you’re being paid enough

In South Africa, we have a saying that goes, “Wathint’ umfazi, wathint’ imbokodo” (You strike a woman, you strike a rock.” Excuse me?! No! You strike me, you strike a woman, a human. You strike my softness and my vulnerability. You steal away what little security I think I have. You cause me harm and pain. You traumatise me. You trigger fear in me. And your actions affect how I live my life, how I think, my relationships and the decisions I must make daily.

We didn’t choose to be strong or as tough as rocks. We had no choice. Racism forced it upon us. Misogyny forced it upon us. Gender-based violence forced it upon us. Being single parents who carry a load no one should ever have to carry alone forced it upon us. Being breadwinners and being disproportionately underpaid forced it upon us. Our families that believed in keeping the peace more than keeping YOUR peace forced it upon us. Society’s double standards on any and everything to do with us forced it upon us. We didn’t choose this. Nobody would choose this.

The next time you catch yourself about to tell a Black woman she’s strong/resilient, try saying, “I can’t imagine what you’ve been through. I hear you when you say it’s been hard. What can I do to help?”

I was sitting on the floor in my mom’s room last year, lost in my thoughts and she asked what was on my mind. I said, “I’ve had to deal with having an absent father who won’t even acknowledge the hurt he has caused me. When I told him we need to have a conversation about our relationship, he said, “let’s chat when we meet”, knowing that meeting wouldn’t happen.

I may not consciously remember it, but my subconscious mind knows our home was bombed and then burnt to the ground. I’ve had to navigate being in a “mixed-race” primary school where I lived in the ‘burbs and my Black friends lived in the ‘hood. I couldn’t connect with my Black friends on weekends or holidays, so I needed to have friends on both sides.

My Black friends literally bullied me and threatened to beat me up for being friends with white people. I was ten years old. I lived with you and your longtime boyfriend for over two years, and he never treated me like his child. He never had time for me or showed any interest. When I was twelve, I had a gun held to my head by a man who wanted to force me to agree to be his girlfriend. At twelve years old, I had to choose between my life by a decision I had been violently forced into or taking the risk of dying because I refused. At twelve years old, I put my money on death.”

A few months before this conversation, I had told her about my suicide ideations. I shared how I had planned it twice and attempted it once. I had even written a suicide note. I added, “The only thing that still keeps me alive is Refilwe. I know now how much pain it would cause her if I died. If it wasn’t for her, I don’t think I’d still be here. I knew you’d hurt for a while, but you’d be okay. But being here, being alive, was just not something I wanted to do anymore.”

She stared at me quietly for a while, stunned. And then she hugged me so tightly. “How could you ever think I would ever be okay in a world without you?”

I had fallen asleep while locked in the car and when I woke up, I had no idea where I was. I was scared. I wished I could call my mom.

They opened the back door of the car and told me to get out. I didn’t say anything. I was drowning in fear. I instinctively knew what was about to happen and it killed me to know that there was nothing I could do about it. I couldn’t run. There was nowhere to run. I couldn’t scream, there was no sign of human life anywhere near us.

I got out of the car, they demanded that I go and pee. “Don’t do anything stupid. We have a gun, and we will kill you if you do,” they said. And then they giggled. One of them then took out a knife to really drive the message home.

I was still silent. I could feel my tears burning my eyes. I moved a few steps away from them and forced myself to pee as instructed, still trying to maintain my dignity and innocence for just a minute longer. I pulled down my jeans and my panties while making sure I keep myself covered with my t-shirt. They never took their eyes off me.

I pulled my panties and jeans back up slowly. I was desperately wishing I could stop time. I was wishing I could rewind everything and change where I was at the time I was abducted. My mind was racing but blank at the same time. I knew I was in trouble. I knew I was about to be raped. What I didn’t know, was whether or not I would make it out alive.

They hurried me up and told me to get back into the back seat and lie down. The first one pulled down my jeans and my panties, spread my legs and began to rape me by performing c*nnilingus on me. I had no idea what was happening. I just lay there, frozen, while tears ran down the sides of my face. Then they began taking turns raping me by penetration while making the vilest comments. It excited them, and me being a virgin was their bonus.

“You can cry and scream all you want; nobody will hear you. We can even scream with you.”

They moved me from the back seat to the front seat and carried on. I don’t know how long this went on. I remember laying on that front seat in complete despair, completely void of any energy. I was mentally and emotionally numb.

Read more | ‘Firms enforcing return-to-office ultimatums risk losing future top talent’ – executive search firm

When they eventually finished and I was able to get out of that front seat, the first guy says to his friend, “Ey, ndoda, umlimazile.” (“Dude, you’ve hurt her.”) I was confused until I looked behind me. My blood was on the seat and then it began running down my thighs.

I didn’t react. I couldn’t. I felt weak and tired and like I was watching myself and what was happening from outside myself. I wiped what I could and put my clothes back on. That was the first time I had ever seen blood coming out of my lady bits. I hadn’t started menstruating yet.

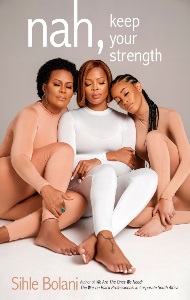

This is an edited extract from Nah, Keep Your Strength by Sihle Bolani, published by SNR Publishing. It is available on takealot.com for R743.